We all fit a demographic. Marketers invent our needs, branding strategies define our identity. Our desires become industries and we become commodity. Quantified, bought and sold, we enroll in the next self-help seminar.

Years ago, a friend and I spoke of our experiences of critiques in art school. She felt frustrated that she was expected to reveal her own personal psychology - fears, memories, neuroses - as if she were in group therapy. I thought it was embarrassing, too. We both agreed that the process of making art was conceptual and intellectual - there was no need to reveal messy inner-motivations. Years later, as I conduct those same critiques, I am still confounded when someone cries or reacts in outrage over things said. A line is crossed. Now that ironic distance is the norm, it's surprising to find that line even exists. But it does. When the line is found, it's personal.

Becoming an artist is a conflicted endeavor. Since Duchamp, the cult of the artistic genius has been in trouble. Technology wages war against originality, forever pushing it closer to obsolescence. What the individual tries to declare, the institution criticizes. These debates, still worthy, have now either spiralled into positions of defense or total detachment. Culturally, this split is played out on a larger scale. In Dreams of Millennium, Mark Kingwell identifies two solitudes, "A profound lack of belief, a cynicism approaching nihilism, now lies alongside the fervent desire to believe that is evident among devotees of angels and miracles."¹ At this millennial juncture, he asserts we either see the world with critical irony where knowing the joke is everything, or we fall into the passion of an all encompassing belief commonly found in fundamental religions and militia groups.

Self Help requests a shift in response.

The process of self-actualization - the struggle to realize ourselves through our work - is not new. However, in today's dehumanized world, acceptable ways for even speaking about self-expression are suspect. Something is missing. We are talking ourselves out of genuine modes of expression and are fearful of forming a relevant language that speaks for ourselves. Though it's precisely what we see when we look at art, it is the individual we face. Art, with its ridiculous and useless methods, reminds us that we are human.

Now that it is common to view processes and transactions through models of efficiency, the artist offers a welcome proposition. Artists are the major players who combat the subsumption of individuality by brand identities. When the terms for discussion are found somewhere between self-help manuals and hermetic theories, it's time to look outwards; to create a new vision and language. In Self Help, a varied group of artists diverge and cross paths to make their own mark on the bottom line. The results range from confessional to analytical. All however, reflect and celebrate the idiosyncrasies of personal experience.

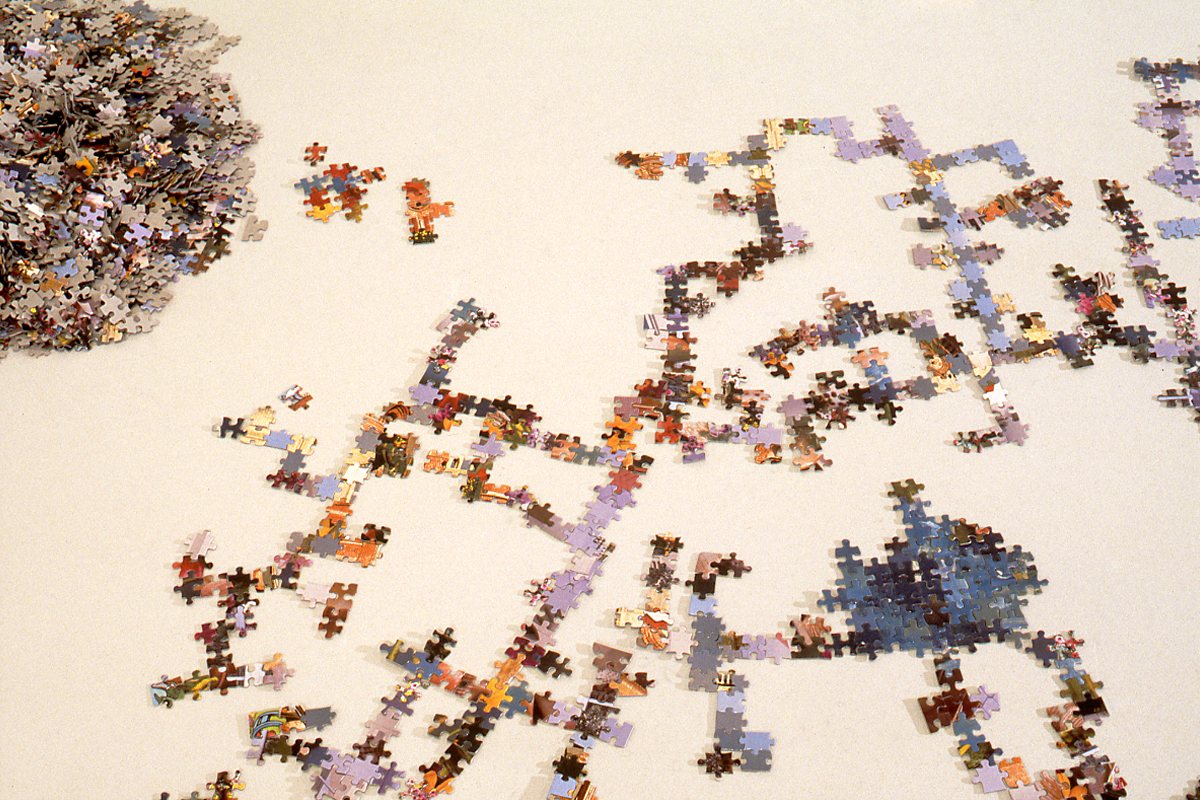

R.M. Vaughan doesn't believe in self-help. The therapeutic industry creates endless tests and questionnaires merely to convince you that you need fixing. Vaughan wants us to help him. In Play It As It Lays, a platform of puzzle pieces entice us with pretty colours and lots of fun. We're invited to go nuts, put the pieces together with him in anyway that we want. The strict order is no one's concern. It's an organic process, just like life. It's fun sitting on the platform with Vaughan - chatting and playing, keeping busy. Here, relationships are forged, trust built. In Pumpkin, Vaughan has created a fiction in which the characters routinely arrive to gather, chat and keep busy, as well. The women are caregivers, mothers passing the time of day while the children play. It's Thursday again, everything seems in order, everything seems safe. For comfort and support, one need only call out.

Joan Dymianiw is letting go. All she really wants is a suitcase filled with things that matter to her. One such thing is a video tape of a collection of home movie clips from childhood - hers and those close to her. It contains a sequence that she was unfamiliar with, that of her then one-year-old brother playing gleefully with a new discovery, a comb. Appearances 1959 is a fractured narrative of that moment. Deftly painted on four panels, the sequence is a blur of boundless energy, echoing both a child's development and an adult's fleeting memory of the past. The boy holds the comb, stares at it, puts it in his mouth. The comb is his. Suddenly, as the comb is taken away, the boy howls. A simply rendered red comb stands apart and, like most of our desires, just out of reach.

Nudging for our attention is Alexander Irving's Debutante. She's at her coming out party and she's behaving like a wallflower. Bulbous and buoyed in her pretty, pink field, this blobular form has a heck of a lot of personality. She, along with her sibling Convalescent, form a family that goes back many generations - they have suffered a great deal. They are survivors. Debutante and Convalescent are from a body of work that Irving started four years ago; an obsessive collection of colourful, bumpy spheres that form endless combinations that multiply, mutate and overtake Irving's studio. They work themselves into your experience and you feel responsible for their state of melancholy. It's enough to make you drink.

In Mini Bar, Irving provides us with an opportunity to do just that. Or does he? Glistening and glittering bottles beckon us to a world of airplane food and lost weekends. Peer into the hole: Mini Bar awaits and offers the promise of friendly cocktail pleasures or a dangerous descent into an addicted state.

Susie Major offers us a diversion of a different kind. In Rest, piles of dishevelled clothes are clumped unceremoniously on the floor, if only temporarily. Her clothes, dropped from the waist down, are left behind like the worries and responsibilities we all wish would happen some time other than now. We see whatever she's wearing that day, whatever she's brought with her. Like going to bed at night, the clothes drop and the drift into dreaming begins.

Rest offers a respite. It helps us cope. We disappear from the task at hand to find a temporary space where nothing happens. While talking on the phone, you speak and your hand wanders into a scribble of pen on paper. Doodle is just that. A quick ball-point pen swirl marks a place on the wall. The arm moving in circles is the easiest thing to do. Major has given us these sites as places from which we can depart.

Stacey Lancaster has spent too much time skulking around in the suburbs staring in mirrors. In the video installation from the trailer series, Untitled One, we enter a dark void only to be engulfed in the likeness of a human face, a mirror image split in half. Slowly it transforms - expanding and contracting - like an encounter with a primitive being. The image is terrifying one born of boredom and isolation. Stare long enough and you turn into something else, someone unrecognizable. Our discovery is palpable, all flesh and hair. She's larger than life, a woman on the brink of recognition, stuck with nowhere to go.

I recognized a subtle feminist work. This is not a picture yelling for attention but one that quietly asserts itself. 'Take me as I am.' Mom is rarely glamorous. She is the history that we try to evacuate on our road to self-actualization. In pop culture we are promised we can be anyone or anything we want to be.

When I was just a little girl

I asked my mother what will I be

Will I be pretty? Will I be rich?

Here's what she said to me

Que sera sera... ²

A child sings "I wonder what I can do" over and over again in Daniel Olson's I Wonder What (reprise). A girl's breathless voice arrests us with her singing, her questioning, "I wonder what I can do?" Wondering with her, we listen to how she articulates her words. We become aware of her breathing. We are lulled by her rhythm. What is that ominous drone underlying her singing?

In 1986, Daniel Olson handed his three-year-old daughter, Corie, a microphone. This is her response. In choosing this particular recording from many that were made, Olson's piece speaks of the fear and joy encountered in a father's relationship with his daughter. A blurry, obscured image of Corie accompanies the recording. There are things we wonder, too. What does the future hold? Over the comforting and disturbing sing-song voice and low pitch drone, one hears the contradictions inherent in childhood and parenting echo throughout the room.

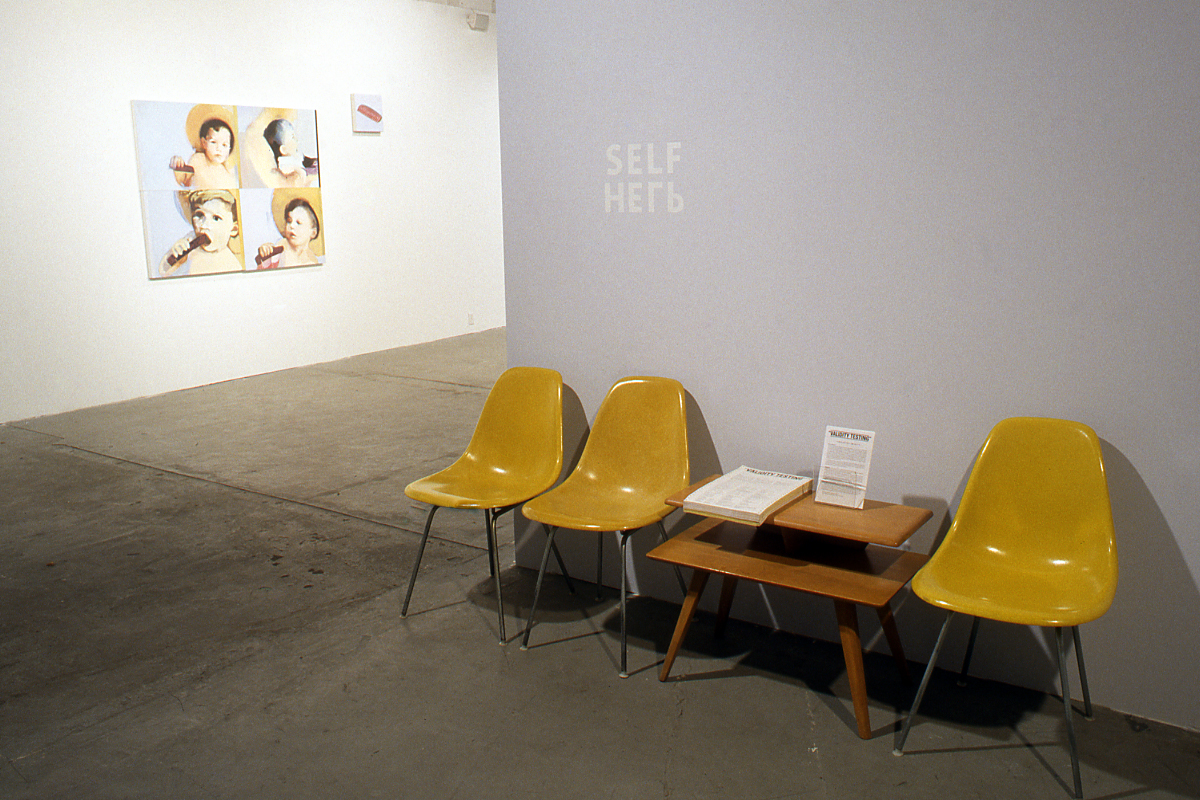

The adult world is a big place, full of responsibilities, deadlines and incapacitating fears of inadequacy. To assist us, the Department of Facts and Figures (a branch of the U.S. government) has been conducting research on our behalf. They have founded the Research Center for Validity Testing. Hall Smyth has been its Director from the start. Smyth brings a "validity test" to Self Help so that we may determine our own validity quotient. Come take the test! Chart your results, compare and evaluate patterns, left and right brain tendencies, find out whether you could be a person with a penchant for cafeterias or whether you're simply misinformed. Learn about yourself to assess your true value to others. Don't worry, you won't fail - you're already a complicit participant in the system. This really is a test like no other. Accuracy is 100% guaranteed.

Early last year, the Ladies' Afternoon Art Society conducted a covert infiltration of a patriarchal authoritarian security system with a cliched feminine construct. They gave cupcakes to cops. In Sticky and Sweet, "Susan," "Susanne" and "Sueann," neatly dressed in their red and white uniforms, decorate a concrete bench at the corner of Robson and Hornby in Vancouver. A crowd gathers as they adorn the bench with icing, sprinkles, little plastic ballerinas, sparklers and candles. Everyone received cupcakes as thanks. People were delighted and confused. So were the cops. Who were these friendly ladies?

On November 14, 2000, the Ladies' Afternoon Art Society will offer "Absolutely Free Lint Removal" in P.A.T.H., (a series of underground pedestrian walkways that link various buildings within the city's financial district). They want to know if they will be arrested for such random acts of kindness. It is, after all, serious business trying to keep suits clean for important encounters. These ladies help others help themselves. They don't want to talk art, they just want to provide a much needed service. Their aim is to engage the community and make it safe and clean for everyone.

The desire to fix things and make them well, the need to soothe and to nurture, has traditionally been a maternal one. Although roles have expanded in recent generations, cliches still exist, and are still reinforced and acted upon. The self-help movement is indeed an industry - and one that caters primarily to women. This movement advocates a turn inward, a concentration on the self, and has been strongly criticized as a diversion from real political issues. "Self-help," the cultural phenomena, it's argued, is a result of a backlash - of empowered women who have turned their back on the movement from which it evolved. Feminism fought for self-empowerment, self-actualization and healing, yet the self-help movement has taken these pursuits and commodified them, made them trivial, rendered them impotent.

Much can be learned from this evolution - of how powerful ideas are usurped and assimilated by market forces. Advocating a means for speaking genuinely about the self (in a progressively globalized world where homogeneity rules) should not be confused with an apolitical desire to turn inward. Speaking for - and about - a human struggle through a personal language is indeed relevant, resonant and powerful.