In "Push Play", the artists explore how the time-based motion of video and the stillness of the painted surface inform and inspire each other. The luminance of video is an ethereal realm animated by electricity, offering painting another surface in which to refer. The tactile and static realm of painting inspires the immaterial world of video, and magnetically binds them together. In turn, the action of video invisibly energizes the substance of paint by inspiring these artists to work with the added dimension of motion.

- K.H.

Brochure Text by Katherine Harvey

Push Play

Although the relationship between painting and photography has been examined exhaustively, the connection between painting and video is relatively uncharted terrain. In Push Play, the artists Marie de Sousa, Michelle Forsyth, Mara Korkola and Melinda Morey explore how the time-based motion of video and the stillness of the painted surface inform and inspire each other. Each artist in this exhibition examines the constant state of flux that exists in familiar environments of their past or present by creating a dialogue between painting and video that defines the material parameters of both media while connecting their aesthetic concerns.

Record

Harkening back to her childhood spent living on a sailboat, Michelle Forsyth explores the undulating topography of water in hypnotic video shots of oceans and aquariums. Using her computer to build intricate geometric patterns, she creates positive and negative spaces that frame the video clips of water. The saturation and opacity of the images of water continually change as they are filtered through these decorative screens. In her paintings, Forsyth replicates these digital pixels with free flowing pigment, thereby creating tension between the liquidness of the paint and the rigidity of the graphic gridlines.

Mara Korkola’s night photography of the familiar roads she travels is the inspiration for her enigmatic paintings. She captures dynamic images of highways and gasoline alleys, pointing and shooting the camera out of car windows. Her videos mark the natural extension of her fascination with the motion of cars as they dissolve into the haze of street lamps and shimmering asphalt. In her paintings, she then further abstracts the play of headlights flickering in the dimness with loose brushstrokes that skip across the surfaces of small wood panels.

For one year, at three-week intervals, Marie de Sousa photographed a specific location in her neighbourhood park, and used the succession of photographs as source material for a single painting that evolved and changed like the seasons. She documented her painting process by taking one still shot for every fifteen minutes of time spent painting. De Sousa’s work accounts for the passage of time as she collects video stills while the paint layers accumulate.

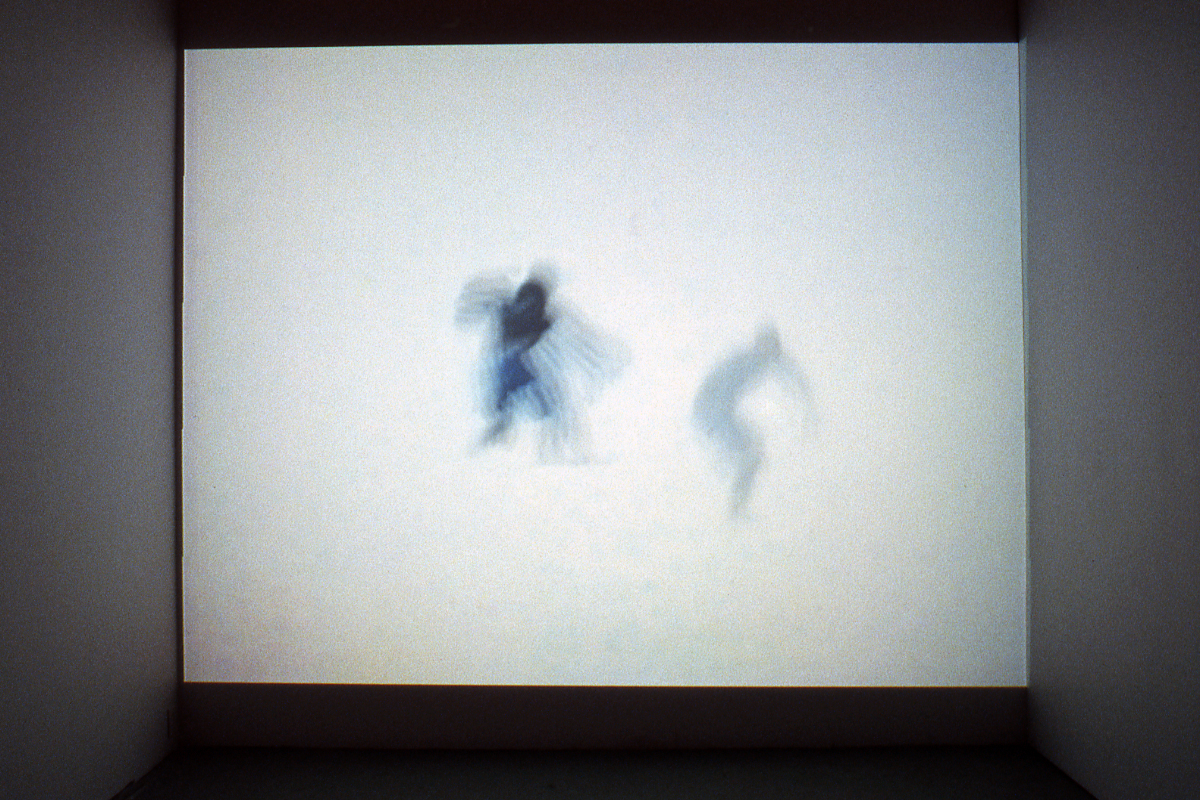

Melinda Morey videotapes fellow surfers riding ocean waves, and through a meticulous editing process, she erases, frame by frame, the surrounding water and sky so that the figures are left to ride an infinite white void. While she was acquiring and editing the video images, Morey began a series of wall paintings that extend this metaphor of transience. The artist strategically paints the bodies in lofty locations or in the corner of a room so that the steep angles of perspective make them appear to be in motion, either falling or losing balance.

Delete

Morey deliberately paints her figures directly on the walls of the gallery knowing that they will be whitewashed when the exhibition is over. Portions of the monochromatic bodies appear to dissolve into the whiteness of the room. The temporary nature of her paintings is a meditation on the impermenance of life and by projecting the video of surfers onto a blank wall without framing them in any way echoes this ethereality. Energized by the motion it contains, the void surrounding the surfers seems to buzz and quake, and in the same way her wall paintings activate the architecture of the gallery. In both media, white space is the solvent that erodes and eventually erases the figures.

The disintegrating agent in Korkola’s work is the shadow of night. As her video camera struggles to discern the highways in the dark, she allows it to randomly shift the images in and out of focus. The blackness appears thick and sluggish; luminescent beams of light are barely able to permeate it. Likewise, the glossy black surfaces of her paintings engulf the shining headlamps and road signs causing them to become indiscernible blurs of light.

De Sousa also obscures her subject matter, not by directly removing information through erasure or twilight, but rather by painting new imagery over top. Referring to the series of source photographs, she applies colours and glazes in an unsystematic manner that constantly revises the landscape. Her ephemeral video projection is a sequential record of her painting process as she gradually covers the scene over with new layers of paint. De Sousa’s video does not strictly fit into the category of time-lapse photography; as it erases and accelerates, the passage of time carries the documentation beyond the boundaries of this genre.

Edit

Through video technology, de Sousa reduces her year-long project to a series of stills, paradoxically making the entire process seem immediate. The twenty-minute tape documents and condenses approximately 260 hours of the painter's labour in front of the canvas. It does not record the additional time involved in making the video, such as the little dance number she performs in between each still, or turning off extra lights, releasing drapes, rolling the paint cart away, then backtracking to get ready for the next painting session.

Like de Sousa, Morey de-emphasizes her laborious video editing in the interest of portraying a seamless event—in her case, the fluid choreography of surfers floating in a void. It took Morey over 200 hours to erase the surging ocean from every frame of her short video. This slow, reductive technique contrasts sharply with the direct, almost calligraphic nature of her wall paintings.

Forsyth, on the other hand, spent far less time designing digital masks on her computer than she did constructing her complex paintings. She developed a lengthy procedure for transforming the electronic images of water into thick brushstrokes that form large knitted patterns. Fragments of colour nudge those next to them, which nudge the next ones, interacting with one another over several months of the painting process.

Play

Forsyth describes her paintings as physical objects having a strong material presence and displays them as unframed rectangles. The flat LCD screens hanging on the wall reference the thickness of her paintings on birch panels. Korkola also shows her roadway videos on monitors of minimal design whose screen sizes match the dimensions of her compact oil paintings. The electronic hardware that these artists use sets up a dialogue with the wooden supports on which the paintings are “played.”

Korkola and Forsyth’s bold applications of paint build up rich pigments into tactile surfaces meant to interact with the body of the viewer. These artists both feel that the same subject matter appears more distant on video because of the glassy smoothness of the screen. The ultra-sheer plane conceals editorial marks as images are translated into pure iridescent light. When shifting her work to video, Korkola finds the potency of her subject lies in its hypnotic visual rhythms—the staccato beat of headlights moving behind trees—which mesmerize the spectator. Similarly, by compositing video clips, Forsyth finds a vehicle for exploring the fluctuating surface of water.

In Push Play the luminance of video is an ethereal realm animated by electricity, offering painting another surface in which to refer. The tactile and static realm of painting inspires the immaterial world of video, and magnetically binds them together. In turn, the action of video invisibly energizes the substance of paint by inspiring these artists to work with the added dimension of motion.

Push Play

Although the relationship between painting and photography has been examined exhaustively, the connection between painting and video is relatively uncharted terrain. In Push Play, the artists Marie de Sousa, Michelle Forsyth, Mara Korkola and Melinda Morey explore how the time-based motion of video and the stillness of the painted surface inform and inspire each other. Each artist in this exhibition examines the constant state of flux that exists in familiar environments of their past or present by creating a dialogue between painting and video that defines the material parameters of both media while connecting their aesthetic concerns.

Record

Harkening back to her childhood spent living on a sailboat, Michelle Forsyth explores the undulating topography of water in hypnotic video shots of oceans and aquariums. Using her computer to build intricate geometric patterns, she creates positive and negative spaces that frame the video clips of water. The saturation and opacity of the images of water continually change as they are filtered through these decorative screens. In her paintings, Forsyth replicates these digital pixels with free flowing pigment, thereby creating tension between the liquidness of the paint and the rigidity of the graphic gridlines.

Mara Korkola’s night photography of the familiar roads she travels is the inspiration for her enigmatic paintings. She captures dynamic images of highways and gasoline alleys, pointing and shooting the camera out of car windows. Her videos mark the natural extension of her fascination with the motion of cars as they dissolve into the haze of street lamps and shimmering asphalt. In her paintings, she then further abstracts the play of headlights flickering in the dimness with loose brushstrokes that skip across the surfaces of small wood panels.

For one year, at three-week intervals, Marie de Sousa photographed a specific location in her neighbourhood park, and used the succession of photographs as source material for a single painting that evolved and changed like the seasons. She documented her painting process by taking one still shot for every fifteen minutes of time spent painting. De Sousa’s work accounts for the passage of time as she collects video stills while the paint layers accumulate.

Melinda Morey videotapes fellow surfers riding ocean waves, and through a meticulous editing process, she erases, frame by frame, the surrounding water and sky so that the figures are left to ride an infinite white void. While she was acquiring and editing the video images, Morey began a series of wall paintings that extend this metaphor of transience. The artist strategically paints the bodies in lofty locations or in the corner of a room so that the steep angles of perspective make them appear to be in motion, either falling or losing balance.

Delete

Morey deliberately paints her figures directly on the walls of the gallery knowing that they will be whitewashed when the exhibition is over. Portions of the monochromatic bodies appear to dissolve into the whiteness of the room. The temporary nature of her paintings is a meditation on the impermenance of life and by projecting the video of surfers onto a blank wall without framing them in any way echoes this ethereality. Energized by the motion it contains, the void surrounding the surfers seems to buzz and quake, and in the same way her wall paintings activate the architecture of the gallery. In both media, white space is the solvent that erodes and eventually erases the figures.

The disintegrating agent in Korkola’s work is the shadow of night. As her video camera struggles to discern the highways in the dark, she allows it to randomly shift the images in and out of focus. The blackness appears thick and sluggish; luminescent beams of light are barely able to permeate it. Likewise, the glossy black surfaces of her paintings engulf the shining headlamps and road signs causing them to become indiscernible blurs of light.

De Sousa also obscures her subject matter, not by directly removing information through erasure or twilight, but rather by painting new imagery over top. Referring to the series of source photographs, she applies colours and glazes in an unsystematic manner that constantly revises the landscape. Her ephemeral video projection is a sequential record of her painting process as she gradually covers the scene over with new layers of paint. De Sousa’s video does not strictly fit into the category of time-lapse photography; as it erases and accelerates, the passage of time carries the documentation beyond the boundaries of this genre.

Edit

Through video technology, de Sousa reduces her year-long project to a series of stills, paradoxically making the entire process seem immediate. The twenty-minute tape documents and condenses approximately 260 hours of the painter's labour in front of the canvas. It does not record the additional time involved in making the video, such as the little dance number she performs in between each still, or turning off extra lights, releasing drapes, rolling the paint cart away, then backtracking to get ready for the next painting session.

Like de Sousa, Morey de-emphasizes her laborious video editing in the interest of portraying a seamless event—in her case, the fluid choreography of surfers floating in a void. It took Morey over 200 hours to erase the surging ocean from every frame of her short video. This slow, reductive technique contrasts sharply with the direct, almost calligraphic nature of her wall paintings.

Forsyth, on the other hand, spent far less time designing digital masks on her computer than she did constructing her complex paintings. She developed a lengthy procedure for transforming the electronic images of water into thick brushstrokes that form large knitted patterns. Fragments of colour nudge those next to them, which nudge the next ones, interacting with one another over several months of the painting process.

Play

Forsyth describes her paintings as physical objects having a strong material presence and displays them as unframed rectangles. The flat LCD screens hanging on the wall reference the thickness of her paintings on birch panels. Korkola also shows her roadway videos on monitors of minimal design whose screen sizes match the dimensions of her compact oil paintings. The electronic hardware that these artists use sets up a dialogue with the wooden supports on which the paintings are “played.”

Korkola and Forsyth’s bold applications of paint build up rich pigments into tactile surfaces meant to interact with the body of the viewer. These artists both feel that the same subject matter appears more distant on video because of the glassy smoothness of the screen. The ultra-sheer plane conceals editorial marks as images are translated into pure iridescent light. When shifting her work to video, Korkola finds the potency of her subject lies in its hypnotic visual rhythms—the staccato beat of headlights moving behind trees—which mesmerize the spectator. Similarly, by compositing video clips, Forsyth finds a vehicle for exploring the fluctuating surface of water.

In Push Play the luminance of video is an ethereal realm animated by electricity, offering painting another surface in which to refer. The tactile and static realm of painting inspires the immaterial world of video, and magnetically binds them together. In turn, the action of video invisibly energizes the substance of paint by inspiring these artists to work with the added dimension of motion.