The Project Room Series presents a number of exhibitions that investigate the recent history of local art.

Project Room Series 4:

This series of exhibitions is an investigation into the recent history of local art. It will examine certain works created in Toronto through the seventies and eighties towards a current rethinking of representation, materiality, identity and art's social function.

Series 4 is an exhibition of work by Andy Patton and Douglas Walker from the 1980's. The show opens on April 29 at 8pm and continues through May 22, 1993.

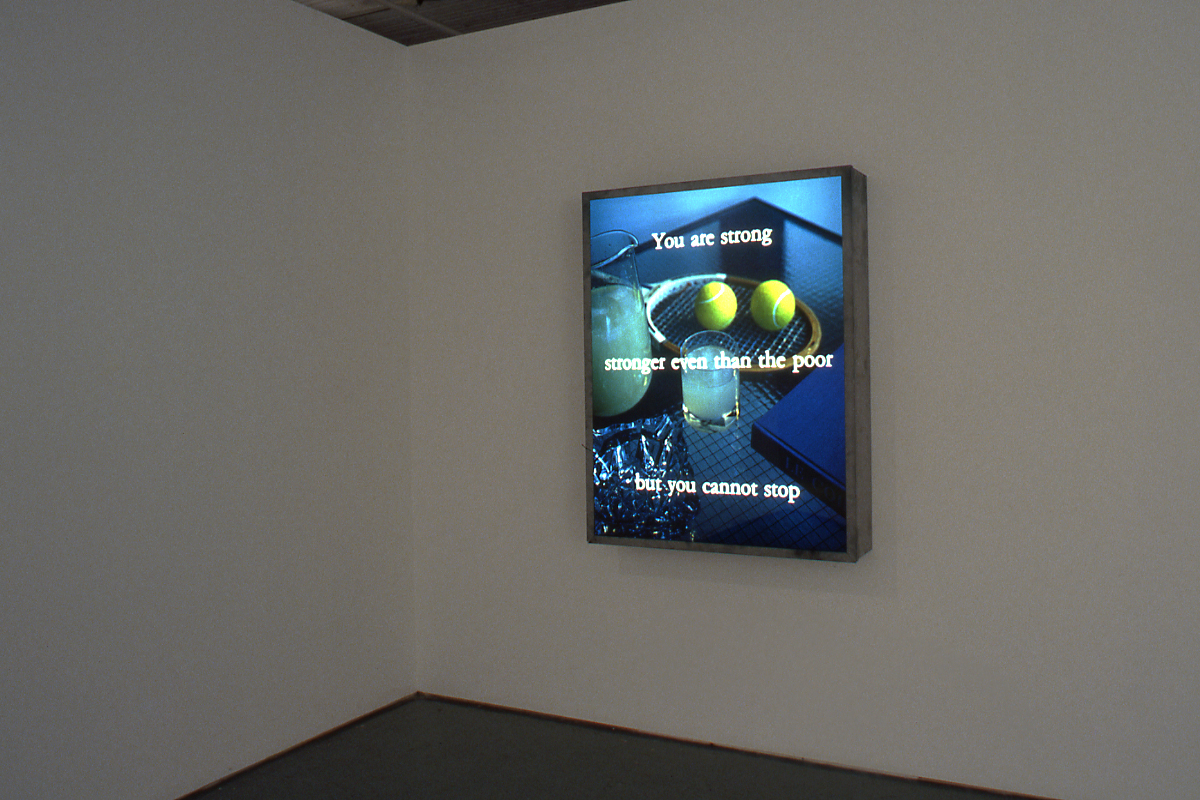

The works in this exhibition interrogate the mediating sites of social power. Andy Patton's light box You are strong...(1981) and Douglas Walker's photoprints (1984 -1986) enact pre-existing cultural formations, such as corporate advertising or the sensibility of adolescent boys. Though formally disparate, these works both function to destabilize these encoded social representations.

Patton's light box, a form now understood as an art mode, was in 1981 instantly recognizable as the form of contemporary advertising display. incorporating this structure, Patton constructs a relationship between image and text which questions the stability of representational meaning.

Walker's black and white photoprints from the mid-eighties are produced in a drawing style recognizable as a form of adolescent expression. Scratched across the surface like personalizing marks on school desks or lockers--tattoos, heavy metal lyrics or biker icons form a compendium of 'dirty white boy' imagery. Walker however undermines the apparent heroic posturing of this imagery with a self conscious anxiety.

While both works resist the assumption of a universalized audience, they proceed from very different cultural sites: Patton from the dominant site of advertising which produces mainstream values and Walker from the position of self conscious subcultural resistance.

Mercer Union has produced a publication documenting each of the Series exhibitions.

Brochure Text:

Project Room Series 4

The works in this exhibition interrogate the mediating sites of social power. To this end Andy Patton's light boxes (1981) and Douglas Walker's photoprints (1984-86) are constructed in the manner of prevailing representations of desire. In different ways these works enact preexisting cultural formations rather than offering any transcendent analytical critique of their operation. They destabilize encoded social representations through which authority is constructed, such as corporate advertising or the subculture sensibility of adolescent boys.

Produced subsequent to a series of anonymous street posters, Patton's light boxes mark a return to the gallery and we!e part of a general local move away from the hegemonic aesthetic of authenticity and authorship associated with performance and video art in Toronto at the time. The light box photograph in this exhibition rehearses an image of the "good life", recognizable as deriving from a contemporary cigarette advertisement. A tennis-racket, pitcher and glass of lemonade, a book and an ashtray are arranged on a glass coffee table; undeniably emblematic of leisure. Superimposed over this image is the text "You are strong/stronger even than the poor/but you cannot stop''. Patton created this vague capitalist commentary by extracting parts of the text of a Superman comic in order to circumvent the received narrative of a particular language of power.

Though now an established art form, the light box in 1981 was instantly recognizable as a form of contemporary advertising display. Patton's use of non-invented imagery and his incorporation of manipulated text produce a temporary illegibility, thereby Inserting ambiguity where one would expect explicit meaning. It is a non-directive posing as a directive and so operates in resistance to the instrumentality of advertising. If advertising creates a seductive relationship between image, text and audience, the text in the piece reflects upon itself and by unwrapping its own structure encourages doubt regarding the stability of representational meaning in such a state of unending production.

Walker's black and white photoprints from the mid-eighties share a similar concern of enacting an already existing form of culturally specific representation: a drawing style recognizable as a transgressive form of private adolescent expression. Rather than an easy consumption of working class taste, however, the overwrought detailing of the surface claims an allegiance not only to a style but also to an obsessive activity. The gouging gesture of the hand is resolute!y etched, like personalizing marks on school desks or lockers, in elaborate patterning across the entire surface of these large format photoprints: tattoos, heavy metal lyrics or biker icons form a sort of compendium of "dirty white boy" imagery. In the context of the entire series of photoprints, this imagery forms a type of cycle which describes a seemingly subconscious awareness of masculinity as constructed against "the natural."

In an image of masturbatory ecstasy, a ghost-like figure decorated in stylized organic patterning embraces the limp body of an adolescent boy with one arm and thrusts its fist through his bleeding pelvis with the other. The boy's "Cat" cap, a symbol of class and concomitant desire for conquering machines, becomes the marker of the alienation of the male from the organic that is prevalent in the imagery of his related works of this period. As a kind of truism, the portrait of a woman in another image, becomes the location of youthful male anxiety. Her face, rendered in graphic simplicity, is covered in tattoos: down her nose is a sword with the inscription "Fuck all", on one cheek is written "Death is Certain/Life isNot" and across her chin are the words "Yeah, I walk in the Shadow of the Valley of Death and am Scared Shitless". While the expected content of such a style is a celebration of transgression - either private fulfillment or exhibitionistic display - throughout this series,Walker's imagery undermines it's apparent heroic posturing and complicates his participation with self conscious anxiety.

Both Patton and Walker create performative circumstances which highlight the consensual nature of representation. They resist the assumption of a universalized audience and proceed from very different cultural sites: Patton from the dominant site of advertising which produces mainstream values and Walker from the position of self conscious subcultural resistance. For both, however, this inhabitation is marked by an uneasy fit.

- Sharon Brooks