East & West Galleries:

In MAKING SPACE, curator Joan Borsa brings together photographic installations by four women artists from varying regions of Canada and the United States who share an exploration of women's perceived and actual social space.

The work of these four artists, Suzanne Lacy, Susan McEachern, Frances Robson and Honor Kever Rogers, addresses cultural interpretations of women's experience, and the distinction between popular notions of the 'feminine sphere' and women's more authentic representations of lived experience. In each case, the artist begins with a situation close to home, either their own particular circumstance or a situation they are directly involved in. Rogers and McEachern deal with the domestic sphere the social space that women have most frequently been associated with. In The Brooding Rooms, Rogers, a Saskatoon artist, explores the complexity of motherhood. Beginning with the popular notions of home as a safe shelter, Dartmouth artist Susan McEachern discloses the psychological implications of women's isolated existence within the nuclear family in On Living at Home.

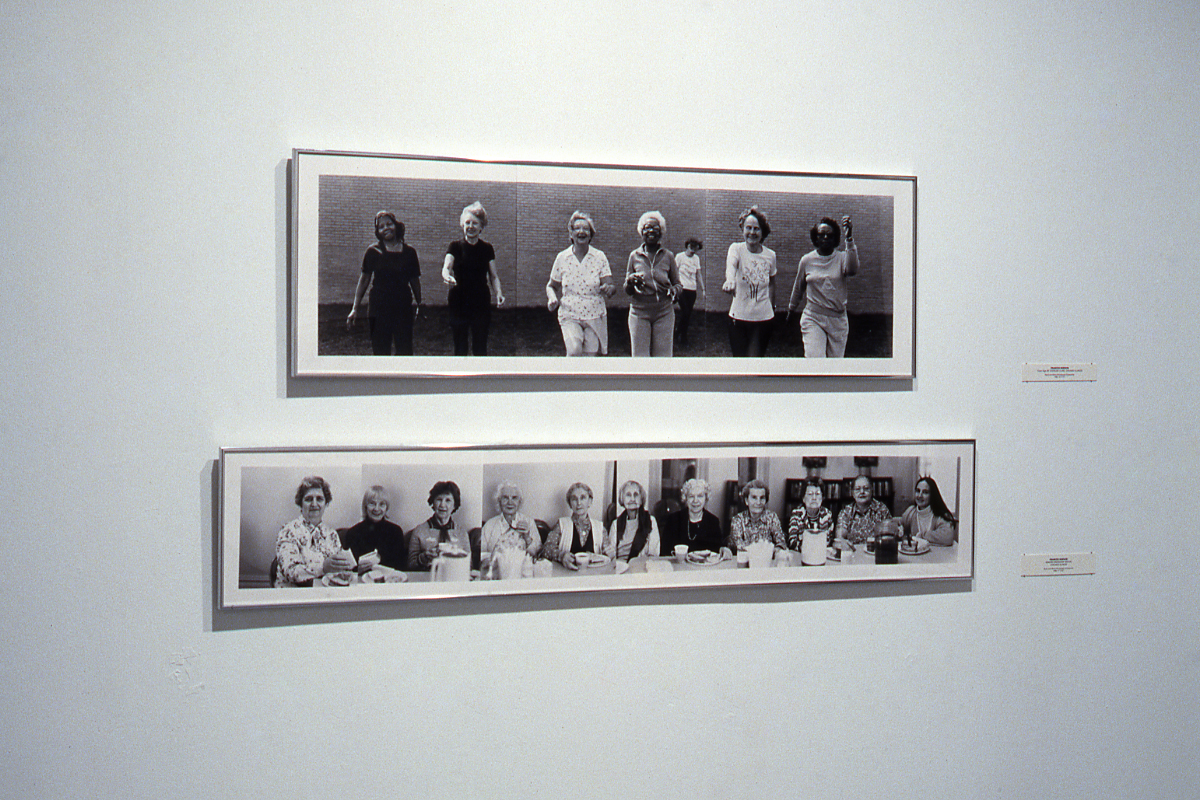

By contrast, Robson and Lacy take the woman out of her home and physically locate her in a traditionally male, public realm. In Women and Community, Saskatoon artist Frances Robson presents panoramic portraits of women's groups in Saskatoon, portraying the individual as part of a larger support group and exploring women's relationships with other women. The photographs in The Crystal Quilt, a performance by California artist Suzanne Lacy, document the interaction between 400 older women who came together from different communities to address issues of aging. In each body of work the artist breaks down and crosses-over traditional boundaries of women's experience.

"The exhibition title, MAKING SPACE, refers to a process - a shift in our consciousness - a breaking down of rigid borders between traditional notions of masculine and feminine - an opening up of space for voices that have long been overshadowed. Finally, we are 'seeing' the ways in which history layers over certain stories, excluding and devaluing their presence. But it's not simply a matter of opening up space within current structures, 'allowing' new voices 'in' - the structures themselves contain limits, some stories cannot be told in the old ways." - Joan Borsa, Curator

MAKING SPACE is being organized by Joan Borsa, an independent Canadian curator, for Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, British Columbia, and will be accompanied by an exhibition catalogue. In conjunction with the exhibition, a public talk by curator Joan Borsa and visiting artist Susan McEachern is scheduled for Wednesday November 16 at 7:30 pm at Mercer Union.

REVIEW

ALLEGORICAL INTERVENTION

Vanguard, November 1988

by Petra Watson

You get older in other people's eyes; you don't see yourself as old. You look out the window not the mirror anymore.

- participant in The Crystal Quilt

In Freud's lecture on "Femininity" the position of the woman as subject is denied by his notorious statement: "To those of you who are women this will not apply-- you are yourselves the problem." We who are "the problem" are assigned a 'space' coded within an economy of sexual inequality that functions to limit women's participation in society and misrepresents women's articulation of their own experience. Socially constructed representation has codified women's experience within the constraints referred to by Laura Mulvey as a certain "masculinization" of spectatorship. As the male is associated with a presence or a marked economy of identification the female is left to find comfort as the other.

To defer (or defeat) conceptual and experiential (en)closures feminist theory has recontextualized its own marginal terms. Giving a privileged position to difference, rather than hierarchical oppositions re-evaluates the patriarchal designation of women within the subjective and objective position defined by Freud's "problem". But this notation of difference problematically defines women's 'femininity' because as Luce Irigaray outlines, the rationalizations of inequality are deeply interconnected within patriarchal codification:

The masculine can partly look at itself, speculate about itself, represent itself, and describe itself for what it is, whilst the feminine can try to speak itself through a new language, but cannot describe itself from outside or in formal terms, except by identifying itself with the masculine, thus by losing itself. Irigaray and other feminists (especially those writing under new French isms') attempt to disengage the mediations of patriarchal presence by questioning the validity of the difference within identities. Theorizing women's presence must posit a symbolic re-ordering as a denial of objectification. This position is not unusual for women; personal history merges into women's history to destabilize the 'within' of dominant patriarchal discourse.

"Making Space" presents a re-reading of this process of certifying difference, not as a valorization of separateness - an apart - but as an intention to affirm presence. In seeking this placement for women the very structure of the symbolic shifts. As curator, Joan Borsa writes:

It's not simply a matter of opening up spaces within current structures, 'allowing' new voices 'in', the structures themselves contain limits, some stories cannot be told in the old ways.

This process of signification must become allegorical because it can exist only within hegemonic conditions. As an allegorical intervention, "Making Space" calls for an awareness of difference: the need to maintain signification of the way things are becomes secondary to the demand for signification of a quite different order. To again quote Borsa:

The artists in "Making Spaces" begin with ordinary everyday experience, but something about it is non-ordinary. We recognize the polished green apples in the bowl on the kitchen counter but the space around them is more claustrophobic than we remember, the abandoned doll lying at the top of the stairs is darker than popular images of childrearing; the panoramic portraits of diverse women's groups push against images of women's isolated existence and the larger gathering of spirited elderly women is not quite how old age appears in the media.

This self-conscious position of allegory reinterprets the "problem" of women's representation, or the absence of the female as both subject and object within discourse, by exerting a presence as an allegorical codification that reveals a gap or distance (making space) between sign and referent.

In selecting artists for "Making Space", Borsa suggests the mobilization of two forces. Susan McEachern and Honor Kever Rogers situate their work in the domestic sphere, but a domestic sphere riddled with contradictions between private and public, iconic and spatial characteristics. Suzanne Lacy and Frances Robson explore relationships between women and how women are situated within a public presence of signification.

McEachern's On Living at Home is a photo-series divided into four parts or aspects of the domestic environment. McEarchern's early work focused on exposing the conditions of unpaid labour within the domestic sphere as a link between the division of labour and sexual inequality. In contrast, On Living at Home, is not satisfied to present the inequalities of the traditional social organization of the family, but focuses on a semiological analysis of the modes of production and reproduction within a political economy textualized as masculine and feminine.

Part One, Agoraphobia, asserts an overall metonymic reference between women's absence and fear of public space - the visibility denied and the resulting role of secondary status. But what is revealed is not the defeat of one sex by the hierarchical interests of the other sex, but a repressed state which is the failure to recognize identification with one's own sex.

McEachern's text supports this: agoraphobia is often supported or reinforced by a spouse with a complementary problem and with an unconscious investment in the continuation of these symptoms. But, finding paradoxes 'within', McEachern states that agoraphobia may also result in what can be described as a strike action by the housewife. If she refuses to participate in her role as the consumer of goods for the family unit a necessary component of the division of labour has broken down.

In Part Two, Three, and Four, Domestic Immersion, Media Consumption, and The World, the division of labour and sexual inequality in the home is shown as being instrumental in structuring the hierarchies of the outside world. The economic order is revealed as dominated by complex organizations and representations which cannot function without the services of women--that is, services through which the interests of the public sphere are continuously reproduced and the dependent services of both the private and public sphere are fulfilled by women's oppression.

Honor Kever Rogers' photographic installation is composed of seven panels, each representing a room or 'space' of the domestic sphere. The Brooding Rooms: Mother-and-Childhood Reassembled address the conditions of reproduction and mother; as the framework for specific social relations. Rogers assembles an "archeological dig" of the artifacts of a mother-child relationship. The translation of these artifacts as memories of both biological and social roles is synthesized and mediated through a vertical, panoramic format.

Suggestive and heuristic, this photo installation develops a means to transcend or define gaps in the reductionism which has narrowed the experience of motherhood to a mythos which limits women's acceptance; and participation in all areas of society.

In keeping the inquiry within a presence for itself, Frances Robson explores women's relationships with other women. Women and Community is composed of eight black-and-white panoramic photographs of women's groups. These groups were formed to develop social, career, and cultural interests. The panoramic format allows each of the women to occupy an immediate position of privilege within each group.

Suzanne Lacy's photographs and texts document the performance piece, The Crystal Quilt. The 1987 performance took place in the Philip Johnson designed, glass-topped, IDS Centre in Minneapolis. The indoor reception area is covered with a red and black carpet. Within this public space were placed 150 tables, covered with black cloths.

The 350 performers, all elderly women are dressed in black. When the performance began, four women sat at each table to unfold the black cloth revealing red and yellow patterns of colour -- the traditional spatial designs of a quilt appropriate the public space. This pattern is completed by the actions of both participants and the audience.

The spatial movements and design (form) of the performance assert a pattern which re-connects or re-evaluates an ordering or system that is asymmetrical and exploitative in structuring sexual hierarchies: elderly women are the most marginal figures within an already subjugated group. As patriarchal interests have subordinated women within social formations that usually remain immersed within the private sphere the power of the performance is that it reaches down through layers of gender subordination.

Lacy's quilt like the show itself, connects aesthetic revitalization with an analysis of power that is then localized within specific institutions of both public and private identification. "Making Space" juxtaposes a presence 'within' difference to suggest that the signification of "masculine culture" is tautological; women in contrast must allow for the differential of "making space" or the identification of signs within closures.