"You're like the invisible friend I had as a kid. Except you dress better."

Brochure Text by Kim Simon

On my less cynical days, I imagine art galleries as part of the public sphere, social spaces where relations of both affinity and conflict are played out through dialogue and debate. Social spaces where, through an encounter with art, we play, act out and maybe relearn our patterns of judgment and how we produce meaning. Social spaces where through processes of perception and identification we perform patterns of relations to others. First Person brings together portrait works by five artists who highlight the question of addressing an audience.

Much of the work in First Person can be seen as autobiographical. However, each of the artists exhibited are proudly and painfully aware of what it means to attempt such a communication within a society of spectacle where identity often becomes simply another product for consumption or just one more arbitrary sign. While the interpretive space of an art exhibition is clearly not immune to a mode of attention based on spectacle, it is exactly within this tendency towards an objectifying and reductive consumption that each of these works becomes compellingly resistant. Refusing the project of summarizing themselves for us, their modes of direct address block our unconscious consumption and make us aware of the way we relate and perceive.

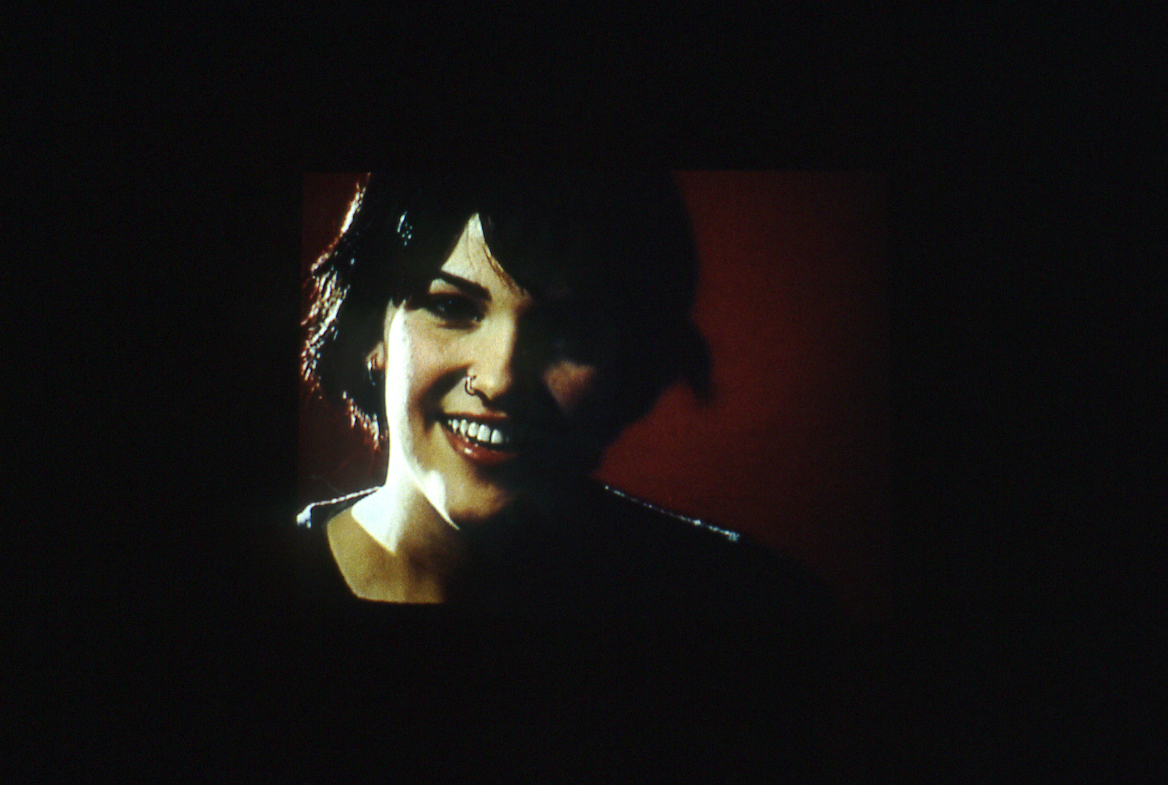

In her Monologue Series, kim dawn presents an installation of three short videos each to be viewed by one person at a time. Each unedited monologue shows a close-cropped portrait of dawn speaking unrehearsed on several themes, looking directly at the camera and through to a potential listener. As dawn recounts her memories of all the cats she has owned, all the therapists she has worked with, and the particular candy she likes, we’re asked to be there for her stories — to listen like a friend to the funny parts, the scary parts, even the boring parts. The intimate and at times confessional nature of dawn’s monologues demands a consideration of what is asked of us as viewers when experiencing the presentation of other people’s identities.

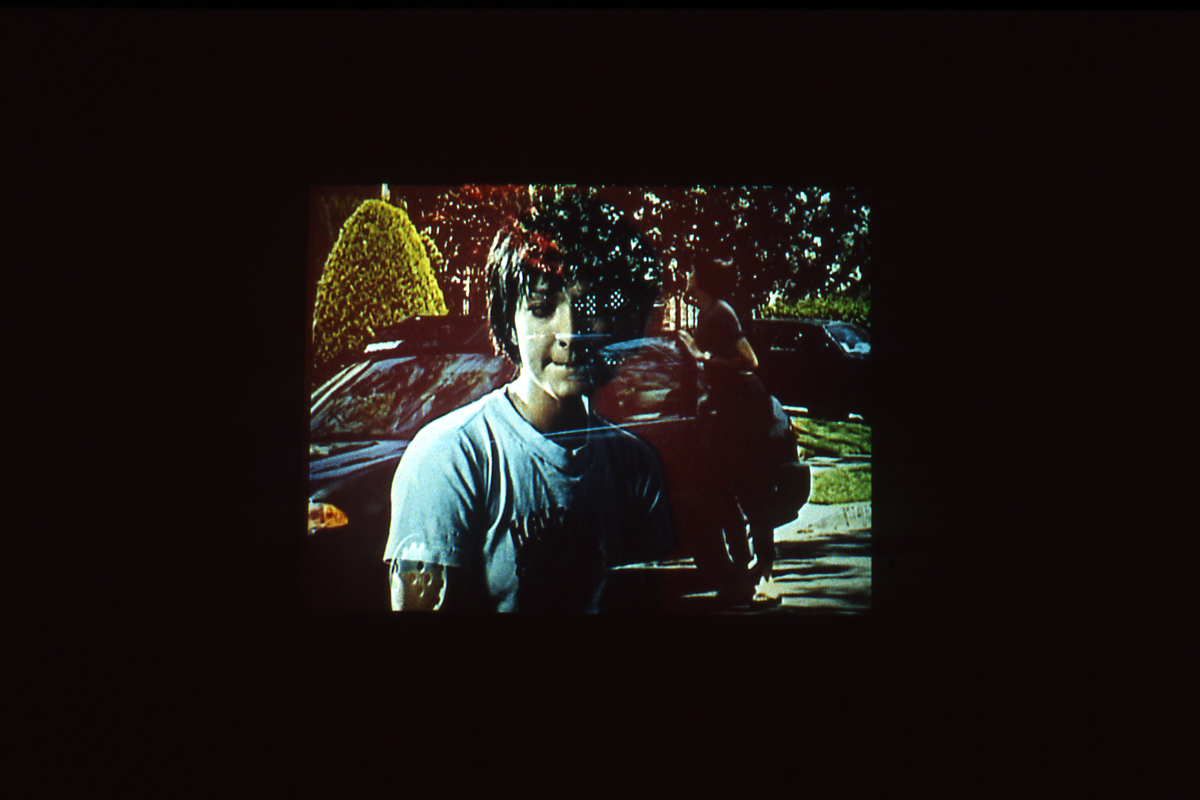

Kerry Tribe’s video Double, like dawn’s work, recalls the direct address of early performance art video. Five women who look a bit alike reflect on topics ranging from their experience of Los Angeles, to their family background, to the current project they’re working on. Each woman is in fact an actress who responded to Tribe’s casting call to play the part of a “video artist” — to play the part of Tribe. In front of the camera they improvise monologues based on a brief off camera conversation with the artist. Tribe herself never appears in the video, rather she presents a smart self-portrait, amazingly self-conscious of her life and work being interpreted by others, asking viewers to be aware of the fine line between authenticity and performance.

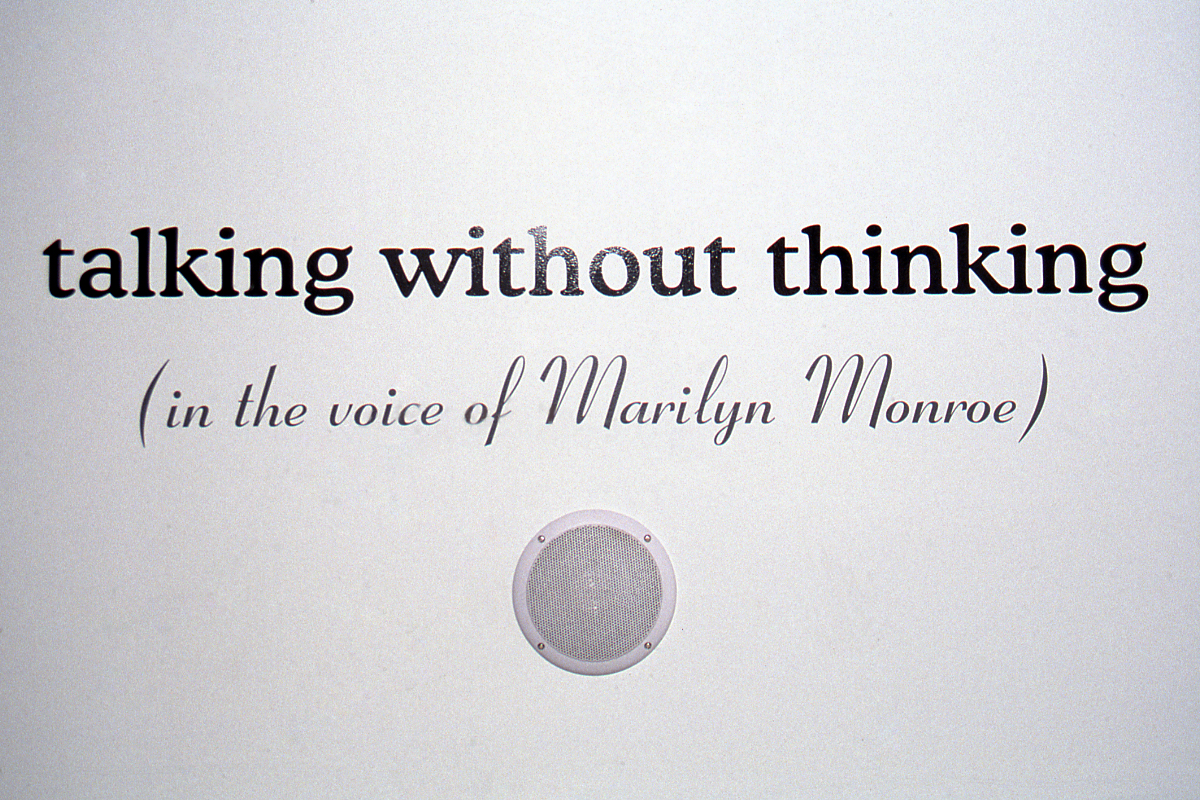

In a related deconstructive turn, Jonathan Horowitz’s sound work Talking without Thinking (in the Voice of Marilyn Monroe) takes us through an unedited, unrehearsed monologue. Painfully attempting to perform the voice of Marilyn Monroe, Horowitz investigates how identity is constructed or perceived through the aesthetics of voice. Questioning the voice, its texture and pitch, as a cultural construct, Horowitz’s work is a performative gesture, its very action and process creating what it struggles to describe. Throughout the first-person monologue, Horowitz discusses the impetus for such an experiment and what happens while he tries to speak in such a voice. What comes out is a simultaneously annoying and entertaining, thoughtful and touching series of associations, identifications, and memories as he tries to describe what changing his voice does to him physically, emotionally, and how he imagines it would mark him socially. The artist’s self-reflexive talk with himself becomes a way to get as close as possible to having a spontaneous conversation about his work with an audience. Horowitz plays with the construct of direct address using the voice to experiment with the possibilities and limitations of communication in contemporary art.

With 15 Minute Portraits, Rebecca Bournigault lets the audience respond and address the work directly. Twenty-four people were videotaped for fifteen minutes each at a time and place of their choosing. What allows for our direct engagement with these people is the work’s installation. The viewer is able to choose which portrait they would like to watch from a stack of twenty-four labelled videotapes. Bournigault’s work becomes a layered portrait, and as we see the artist through her association with her sitters, we see the individual portrait of each sitter, and we become aware of ourselves and other viewers in the gallery. Actively having to select and change, to accept and then pick a moment to reject a portrait, causes a consciousness of what intrigues or repels us — a voyeuristic desire, a compelling glance, a boredom, disgust — Bournigault makes us responsible for who is seen.

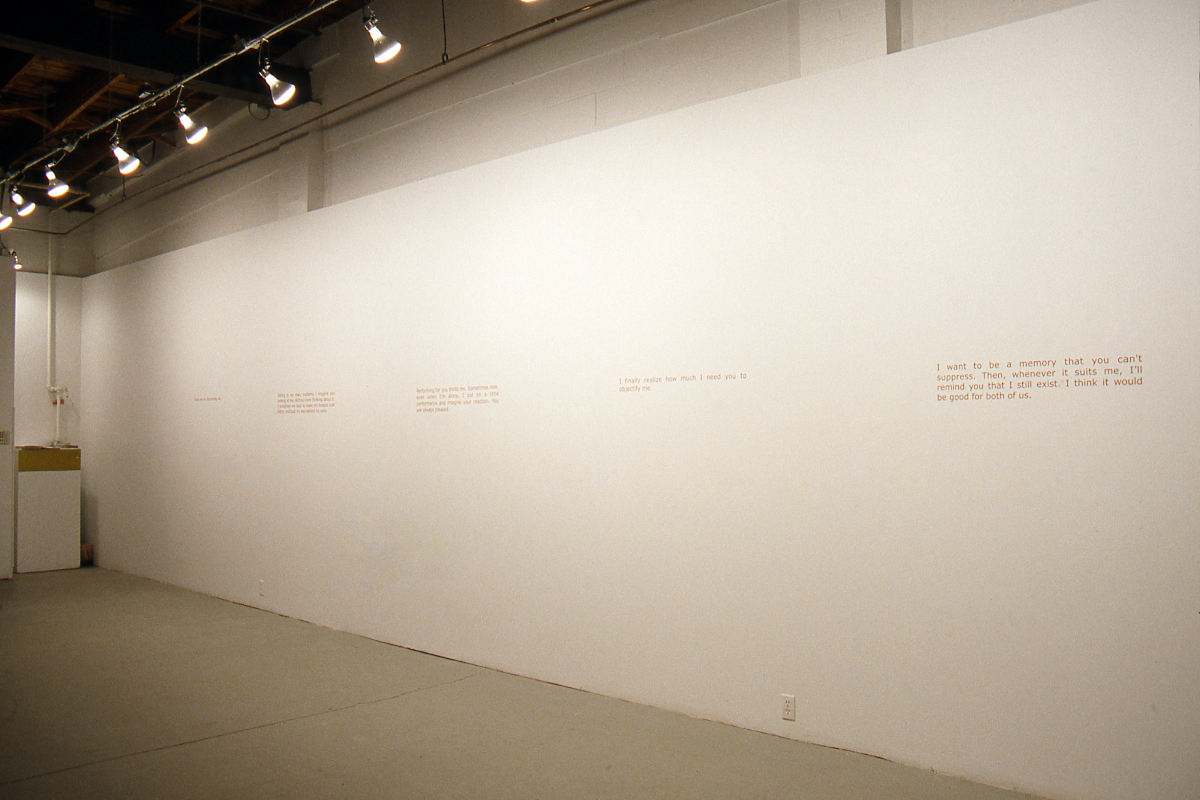

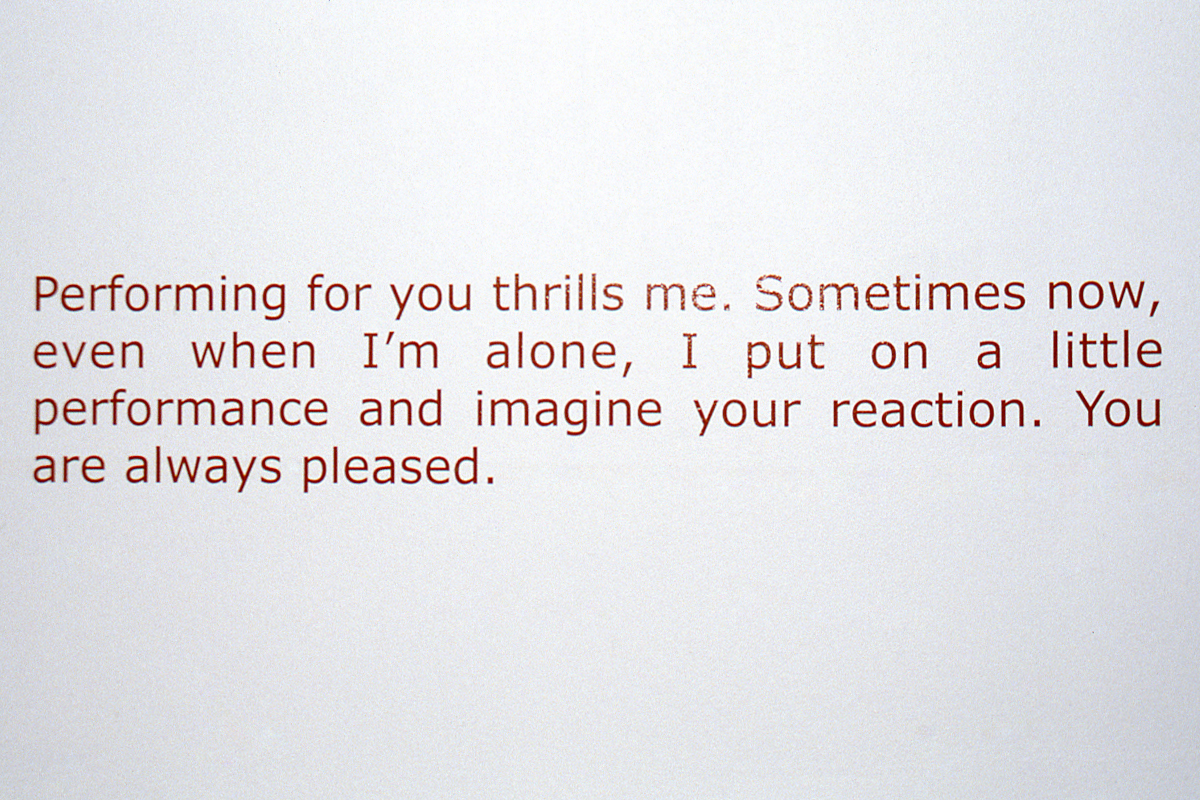

Sharon Switzer’s linguistic portraits take on the first-person voice to engage readers in an experience that positions this viewing as interactive, implicating the gaze of the audience in the subject of her writings. Reading these portraits, we either take on the voice of the “I,” identifying with the narrator, or we become that Other on a pedestal that Switzer’s faceless portraits are so conscious of, that want so much to please. “Thank you for discovering me,” one says, happy for whatever time we offer in our reading. “You’re like the invisible friend I had as a kid. Except you dress better,” another states, as though they’ve anticipated us all along. Clearly embodying a duality that exists in all the work of First Person, Switzer’s text portraits highlight a structural experiment while simultaneously implying the personal in an emotional address.

Using different strategies of direct address and implicating the viewer as subject, the artists in First Person posit a relationship with their portraits. They hope someone is watching and listening. They imagine we have expectations, maybe suspicions, or patterns of identification. They suspect we want to know what the work is about, or that we’re waiting to have something revealed. We may or may not get what we want here, as these portraits tease and the only true revelation becomes a consciousness of how we relate to these works. These portraits offer themselves for engagement, yet mediate their own image, perfectly aware that we are all a speaker, a seer and a seen, playing hide-and-seek with each other.

On my less cynical days, I imagine art galleries as part of the public sphere, social spaces where relations of both affinity and conflict are played out through dialogue and debate. Social spaces where, through an encounter with art, we play, act out and maybe relearn our patterns of judgment and how we produce meaning. Social spaces where through processes of perception and identification we perform patterns of relations to others. First Person brings together portrait works by five artists who highlight the question of addressing an audience.

Much of the work in First Person can be seen as autobiographical. However, each of the artists exhibited are proudly and painfully aware of what it means to attempt such a communication within a society of spectacle where identity often becomes simply another product for consumption or just one more arbitrary sign. While the interpretive space of an art exhibition is clearly not immune to a mode of attention based on spectacle, it is exactly within this tendency towards an objectifying and reductive consumption that each of these works becomes compellingly resistant. Refusing the project of summarizing themselves for us, their modes of direct address block our unconscious consumption and make us aware of the way we relate and perceive.

In her Monologue Series, kim dawn presents an installation of three short videos each to be viewed by one person at a time. Each unedited monologue shows a close-cropped portrait of dawn speaking unrehearsed on several themes, looking directly at the camera and through to a potential listener. As dawn recounts her memories of all the cats she has owned, all the therapists she has worked with, and the particular candy she likes, we’re asked to be there for her stories — to listen like a friend to the funny parts, the scary parts, even the boring parts. The intimate and at times confessional nature of dawn’s monologues demands a consideration of what is asked of us as viewers when experiencing the presentation of other people’s identities.

Kerry Tribe’s video Double, like dawn’s work, recalls the direct address of early performance art video. Five women who look a bit alike reflect on topics ranging from their experience of Los Angeles, to their family background, to the current project they’re working on. Each woman is in fact an actress who responded to Tribe’s casting call to play the part of a “video artist” — to play the part of Tribe. In front of the camera they improvise monologues based on a brief off camera conversation with the artist. Tribe herself never appears in the video, rather she presents a smart self-portrait, amazingly self-conscious of her life and work being interpreted by others, asking viewers to be aware of the fine line between authenticity and performance.

In a related deconstructive turn, Jonathan Horowitz’s sound work Talking without Thinking (in the Voice of Marilyn Monroe) takes us through an unedited, unrehearsed monologue. Painfully attempting to perform the voice of Marilyn Monroe, Horowitz investigates how identity is constructed or perceived through the aesthetics of voice. Questioning the voice, its texture and pitch, as a cultural construct, Horowitz’s work is a performative gesture, its very action and process creating what it struggles to describe. Throughout the first-person monologue, Horowitz discusses the impetus for such an experiment and what happens while he tries to speak in such a voice. What comes out is a simultaneously annoying and entertaining, thoughtful and touching series of associations, identifications, and memories as he tries to describe what changing his voice does to him physically, emotionally, and how he imagines it would mark him socially. The artist’s self-reflexive talk with himself becomes a way to get as close as possible to having a spontaneous conversation about his work with an audience. Horowitz plays with the construct of direct address using the voice to experiment with the possibilities and limitations of communication in contemporary art.

With 15 Minute Portraits, Rebecca Bournigault lets the audience respond and address the work directly. Twenty-four people were videotaped for fifteen minutes each at a time and place of their choosing. What allows for our direct engagement with these people is the work’s installation. The viewer is able to choose which portrait they would like to watch from a stack of twenty-four labelled videotapes. Bournigault’s work becomes a layered portrait, and as we see the artist through her association with her sitters, we see the individual portrait of each sitter, and we become aware of ourselves and other viewers in the gallery. Actively having to select and change, to accept and then pick a moment to reject a portrait, causes a consciousness of what intrigues or repels us — a voyeuristic desire, a compelling glance, a boredom, disgust — Bournigault makes us responsible for who is seen.

Sharon Switzer’s linguistic portraits take on the first-person voice to engage readers in an experience that positions this viewing as interactive, implicating the gaze of the audience in the subject of her writings. Reading these portraits, we either take on the voice of the “I,” identifying with the narrator, or we become that Other on a pedestal that Switzer’s faceless portraits are so conscious of, that want so much to please. “Thank you for discovering me,” one says, happy for whatever time we offer in our reading. “You’re like the invisible friend I had as a kid. Except you dress better,” another states, as though they’ve anticipated us all along. Clearly embodying a duality that exists in all the work of First Person, Switzer’s text portraits highlight a structural experiment while simultaneously implying the personal in an emotional address.

Using different strategies of direct address and implicating the viewer as subject, the artists in First Person posit a relationship with their portraits. They hope someone is watching and listening. They imagine we have expectations, maybe suspicions, or patterns of identification. They suspect we want to know what the work is about, or that we’re waiting to have something revealed. We may or may not get what we want here, as these portraits tease and the only true revelation becomes a consciousness of how we relate to these works. These portraits offer themselves for engagement, yet mediate their own image, perfectly aware that we are all a speaker, a seer and a seen, playing hide-and-seek with each other.