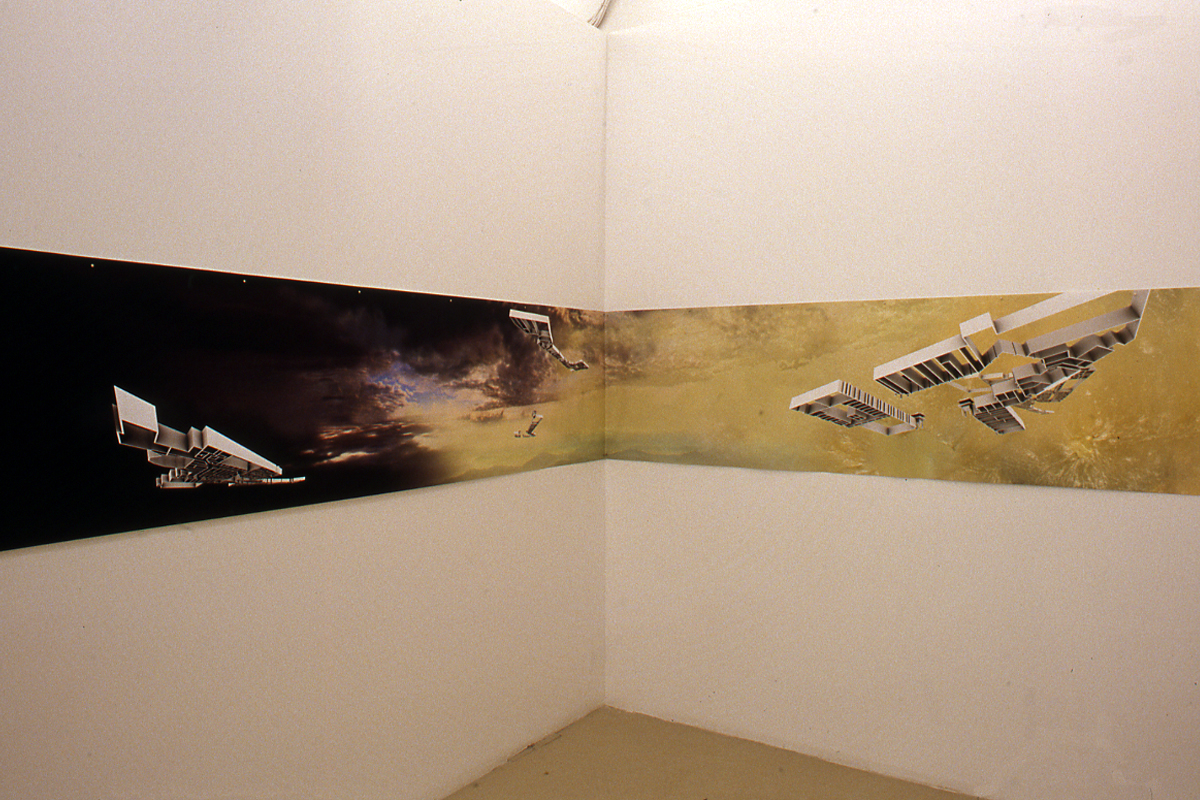

Using suburban 'satellite' chinese malls as the graphic bases of his design, An Te Liu creates a wall script that runs through sections of the gallery. The structural outline of these new asian malls float in an ambiguous landscape becoming the visual material in an unknown terrain. The panoramic scene is reminiscent of science fiction novel covers and film and television depictions of some unknown and new galaxy. The floating architectural structures speak of a somewhat dislocated whole – a self-contained shell in the middle of nowhere. Michael Meredith comes in in the background: floor mats, ambient music, the lighting. Meredith takes over these often unnoticed spaces like an eloquent conversationalist, complimenting Liu’s work and highlighting the gallery as a space.

by Janine Marchessault

In Ether, An Te Liu presents a sixty-five-foot panorama of suburban architectures that appear like spaceships drifting in an ephemeral but emphatically vacant landscape. Based on and traced out of existing urban plans for suburban Chinese malls in the Greater Toronto Area—Mississauga Chinese Centre (Mississauga), First Markham Place (Markham) and Market Village (Richmond Hill)—Ether is structured as a Generic City with supreme banality, a testament to capitalist implosion and the concomitant surrealism of borders.

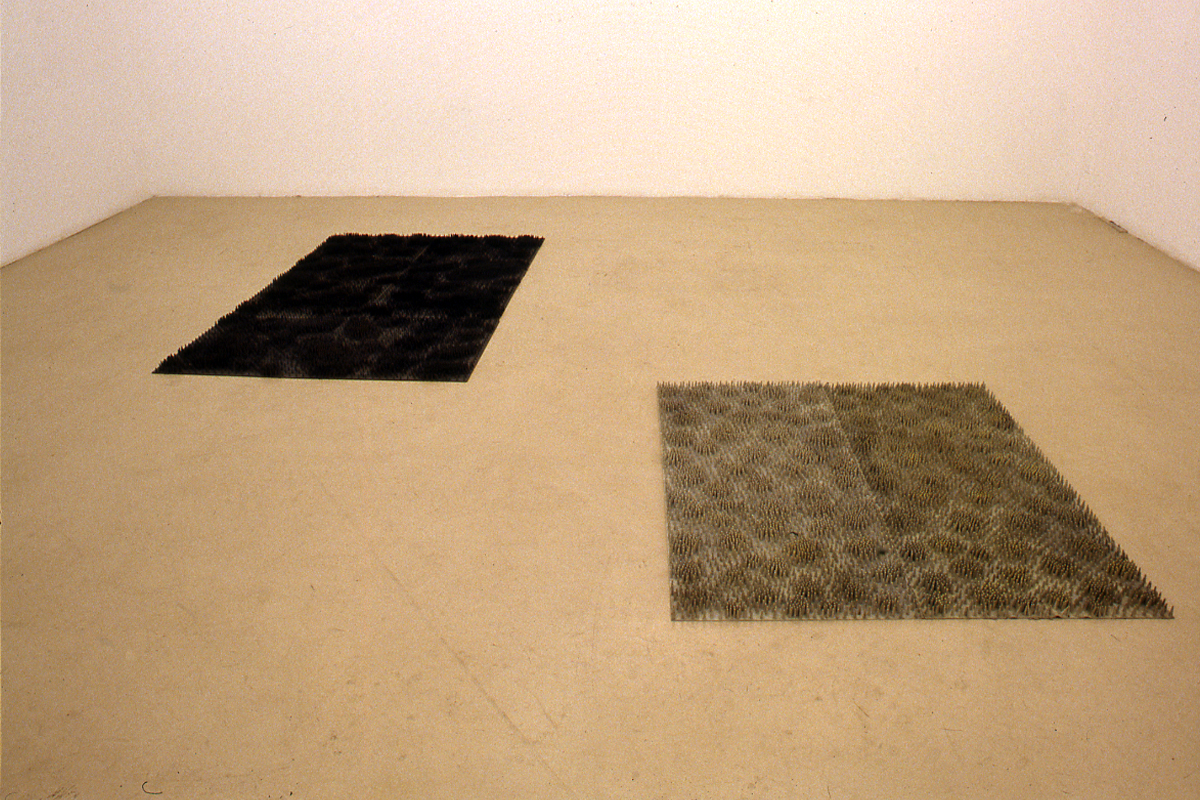

Michael Meredith constructs several works that complement Ether as ironic gestures towards lifestyle and design, highlighting the market fundamentalism of the urban environment as shopping centre. Meredith produces glow-in-the-dark floor mats, honeycomb light fixtures, and a special muzak mix for the gallery. This is literally the environmental condition of Ether’s city. The fixtures from ceiling to floor are drawn out of natural formations that rework rhizomatic clusters. The opposition between glow-in-the-dark floor mats and the light technology is not so much a contradiction as a statement on the randomness and discontinuity of the sensory dressing. Meredith insists on a synaesthetic experience that underscores Ether’s disembodied territories. Yet beyond this, his pieces offer no sensual comfort and the muzak (music produced to increase worker and consumer productivity) echoes the empty figures of Ether’s malls.

An Te Liu’s earlier study of the new formations of diasporic ethnicities in Migratory Studies of the North American Chinatown (2004), inverted the generic enclaves of strip malls by infusing them with the urbane character of Chinatown. In this context, the racialized spatiality of Chinatown (and other such formations like Little Italy, Little India, Little Jamaica, etc.,) is a clichéd articulation of the modern city—the techno-orientalism of the sci-fi film, for example. This cliché belongs to the utopian ideal of the urbane as place of heterogeneous commerce and cultural interface. But more than this, the very title of An Te Liu’s study calls forth both ancient and postmodern cultural practices, that sensational hybridity that in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (a film that seems not to have aged) was said to produce an “eternal present” in which the temporal continuum collapses into an overdetermined present. There is in Ether something largely reminiscent of this science fiction film whose future city refracted the sheen of the computer in a virtual space that was built upward rather than outward simply because the inhabitants had run out of space.

It is fitting that the first study of the North American Chinatown is reconfigured in Ether in a large panorama, the most appropriate form to carry historical narratives of military conquest. The panoramic scene is printed on Tyvek, that Dupont product that Federal Express uses for its envelopes. This industrial material, which is both lightweight and resilient to ensure the speed and efficacy of the global courier service, is unrolled like a continuous scroll across the wall. What has been lost or contained (which amounts to the same thing) in both Migratory Studies and Ether is a history of movement and labour—the early history of garment factories, slave labour, and work camps that underpins the development of Chinatowns in North America. Instead, in both of these studies of urban sprawl there is an “ether effect,” a numbing lack of distinction and affect. The metal outlines of the malls are, as befits the society of the spectacle, both banal and spectacular.

In Ether, the ground upon which the architectural structures unfold is presented as a soft taupe of endless clouds and vague terrestrial formations. The half dozen or so malls appear as metallic braces, extracted and reduced to outlines that float promiscuously over this dematerialized space. In their instrumentality, these forms of life, staged in the middle of nowhere, conjure what Giorgio Agamben has described, as ”dislocating localization,” an expression of the “hidden matrix and nomos” of the political space in which we live. Indeed, this is the hidden force of Michael Meredith’s environment—precisely, the subliminal effects of doormats, light, and music Agamben describes dislocated localization as the space of “camp” which is a pure expression of modernity. Its rise as an architectural and lethal technology coincides with changes in citizenship laws and the denationalization of citizens. It is the ”fourth and inseparable element that has been added to and has broken up the old trinity of nation (birth), state, and territory.”¹ The camp regulates and inscribes order into the life that upsets the relation territory-birth. The process of “dislocating localization” contains all forms of life and norms that fall outside the boundaries of the nation-state. Thus we might say that hybridity, multiplicity, and difference are not produced by global economic flows, by diasporic cultures and technological circuits—the elements of globalization. On the contrary, the political-juridical structure, which defines the present situation, is one of containment, where politics must be understood fundamentally as biopolitics.

The shopping mall and the camp are seemingly located at the opposite ends of the political spectrum of freedom. Yet we must read these two spatial modalities together—their instrumental cartographies, their dislocating order, their strategies of surveillance, their “delirious normative definitions of the inscription of life in the city”² and their conjugation of biopolitics. These all stem from the same political-juridical situation. The works of this exhibition instill this kind of reflection by materializing spaces of instrumentality and functionality that are painstakingly referential. Lest we forget, this is a panorama of Toronto’s suburbs.